One of the worst mistakes a startup can make, particularly at its earliest stage, is to obsess too much about competition. A lot of wise people, including Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, rightfully suggest that you should focus most of your energy on the customer and the problems you’re solving for him or her, not on your competitors.

Having said that, the subject of competition comes up all the time for startups: Investors want to know why they should fund you and not somebody else who seems to do something similar. Your salespeople need to explain how you’re different (and better) every day to potential customers. Employees want to be motivated by the feeling of working for the best company in the industry. And finally, it’s essential to build a product that has a genuine advantage over the other players in the industry. While most of this should be driven by a deep understanding of customer needs, it’s also essential to know what other players in your market are doing to avoid commoditization.

There’s of course plenty of management literature about competitive analysis, differentiation and strategic positioning versus the competition. Most of these books suffer from two issues that make them not overly useful for startup leadership teams: First, they are often written with fairly static, mature markets in mind where building lasting competitive barriers is still possible – not exactly the reality of today’s rapidly changing technology markets. Second, they tend to be heavy on the analysis and light on action. The frameworks proposed by most authors might give you a better understanding of what your competitive landscape is right now, but there’s typically not much useful advice for how to apply these insights into your own strategy and leadership process. Porter’s wildly overused Five Forces framework is the canonical example for a static and analysis-heavy approach.

For fresh thinking, it’s often useful to look beyond the boundaries of your own industry or domain and try to apply principles found elsewhere to the world of startups. A good example are some ideas that were originally developed for military air combat, but are easily applied to startup reality. Of course, military metaphors are a bit overused in business, but only if you’re being too simplistic. The military was the original source of advanced strategic thinking, and there’s still a lot to be learned from this domain.

A few months ago, I stumbled upon the fascinating biography of John Boyd, a legendary military fighter pilot and military strategist (through Venkatesh Rao’s complex, but very inspiring blog). Boyd spent the first years of his career as a pilot and made a name for himself as “Forty Second Boyd” because he was able to beat any opponent in an air combat dogfight within 40 seconds. His advantage was a combination of the daredevilry typically found in fighter pilots in combination with a deep understanding of the underlying principles of air combat. Not coincidentally, that’s a combination you often find in the best entrepreneurs as well.

John Boyd. Outfit not recommended for investor pitches. (Source)

Later in life, Boyd worked as a strategist, engineer and military scholar in the Pentagon and beyond. He is credited with many of the innovations that made the F-15 and F-16 fighter planes possible, both seen as revolutionary designs at the time (although military bureaucracy watered down many of Boyd’s most cutting-edge ideas).

But the most lasting legacy of Boyd’s work is his writing and teaching about new approaches to military strategy. He developed the concept of the OODA loop (more about it below) that brought a highly dynamic and decentralized view of decision making and leadership to military commanders. As a specific example, Boyd is credited with developing most of the American strategy for the successful 1991 first Gulf War against Iraq. The quick collapse of Saddam Hussein’s forces was a direct result of Boyd’s unconventional strategic approach.

That’s all impressive, but what can startups learn from a man like that? There are three main points:

1. Really know your stuff and learn beyond the boundaries of your core expertise.

Most fighter pilots (or so I’m told) are courageous and intuitive people. They spend countless hours flying fast jets, endlessly training the same maneuvers, constantly risking their lives. But few of them bother to learn the deeper underpinnings of their trade. They might know the basics of aerodynamics and plane technology, but in their hearts they are really doers, people who fly a plane with the seat of their pants.

Many entrepreneurs are similar. They want to get stuff done. If they’re technical, they like to write code instead of dealing with boring business stuff. If they’re from the business side, they often like to spend time with customers and investors, come up with new growth hacks or marketing ideas and leave the technical nitty gritty to the engineers. Wether technical or not, many founders can’t be bothered with the details outside of their main focus because they think that all that counts is action in their immediate area of expertise.

John Boyd was different, and that’s what made him so successful as a pilot and later as a strategist. He spent endless hours studying the physics of flying, coming up with his own theories that often resulted in maneuvers nobody had ever considered. In addition, he read very broadly, incorporating ideas from many other fields into his strategies. The results were the standard textbook for aerial combat, used with modifications to this day, as well as several groundbreaking works of military strategy.

But Boyd was not a theoretician. He spent time in a fighter plane whenever he could, testing and refining his theories. He often broke rules that he considered to be outdated, and he constantly challenged his collaborators to go beyond their comfort zone. Most of all, he liked to teach people his best ideas to make them better.

The best entrepreneurs are very much like that – they combine a bias for action with deep and broad understanding. Steve Jobs was known to have a remarkably detailed knowledge of electronic components, which was essential for the success of many legendary Apple products – think tiny portable hard disks for the first iPod or the first multi-touch screen for the iPhone. Elon Musk is obviously somebody who thoroughly understands many aspects of batteries, cars, rockets and so on. He gets deeply (many might say too deeply) involved in the details of Tesla’s production processes and SpaceX’s rocket launches. You can read the biography of any great entrepreneur and you will find somebody who has deep understanding of core topics and broad interests at the same time.

2. Understand your competition and yourself deeply and honestly.

One of Boyd’s key innovations was the energy-maneuverability (EM) theory, a model that mathematically describes aircraft performance. It was useful to develop new maneuvers for fighter planes, but also to understand the limits of performance of any given plane.

When Boyd and his collaborators applied the EM theory in the late 1960s to a data set about Russian MiG fighter planes that they had received from the CIA, they were surprised to find that the latest MiGs outperformed all American planes by a substantial margin, in almost all relevant aspects. This was of course not welcome news in the Pentagon, and they had to fight hard to get acceptance for their analysis. But brilliantly, they developed a simple visualization for plane performance that showed on a single slide which aircraft was superior when you overlaid the performance curves of two planes. It was a painful insight for Pentagon generals, but it led to fundamental changes to huge American defense programs, which in the end led to significant air superiority.

There are two lessons here for startups:

First, be honest with yourself and your team about your competition. Competitive analysis is not a feel-good exercise. Yes, probably every tech startup has that infamous marketing chart somewhere – the feature matrix where your product gets all green checkmarks while your competitors have gaping holes. Don’t forget, that’s marketing, not disciplined competitive analysis. But the other extreme is equally wrong. Many startups go through phases of “OMG, all our competitors are better than us” when nothing could be further from the truth. The solution is to constantly monitor your competition, gather all the data you can get and periodically assemble a robust, honest analysis of your competitive landscape.

Second, find a way to visualize how you stack up against the competition for at least your leadership team, maybe for the whole company. While it’s painful initially to see that you’re lagging in certain aspects, it can be incredibly energizing in the long run as you see improvements over time. A visualization that works well is a spider chart that covers not just product features but everything that matters for winning: Pricing, public perception, funding, team strength, distribution, partnerships. The criteria might differ by market, but it’s essential to define and prioritize them and then follow the same structure over a long period of time. It’s easy to get distracted by irrelevant details, such as a minor new feature a competitor just launched, when it’s the whole picture that really counts.

3. Lead dynamically and surprise your competition.

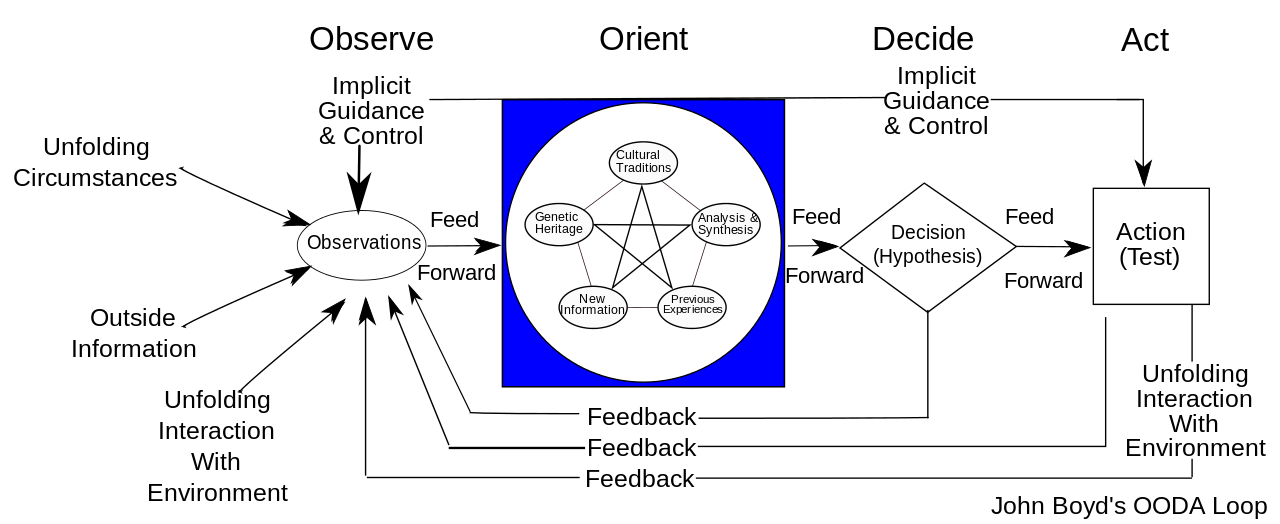

Boyd’s greatest contribution to military strategy is his concept of the OODA loop (observe, orient, decide, act). The fundamental concept might sound simple, almost trivial to a modern entrepreneur well versed in the art of agile management (which was of course largely unknown in the 1960s when Boyd came up with the idea), but the subtle points are what really makes OODA such a relevant concept. Boyd pointed out many times that this concept didn’t just apply to the military, but also to business, sports and any other domain where people compete.

The OODA loop (Source)

The four phases seem straightforward enough:

1. Observe: Take in all relevant information about the current situation.

2. Orient: Make sense of the available information. This is the most complex step because it is influenced by many factors, including the genetic heritage and cultural tradition of the person who does the orienting. This is why sometimes entrepreneurs with a completely non-standard background see entirely different opportunities in an industry, all while having access to the same information as everybody else.

3. Decide: Make a hypothesis on what the best course of action is, given the prior analysis.

4. Act: Implement the course of action, thereby testing how your hypothesis stacks up against reality.

Then, not surprisingly, rinse and repeat. OODA is a highly iterative approach with several overlapping cycles of iteration.

One of Boyd’s key points was how important speed is. If your OODA loop is faster than your opponents’, you have an advantage that is very hard to undo. And even more importantly, if you can carry out actions that your competition never saw coming, you can destabilize them fundamentally.

It’s of course important to point out that this is not the same as reacting hectically to any new development in your market. Quite the opposite is true: OODA is about taking the initiative, about taking control and surprising your competitors. The crucial thing is the orientation phase, where you need to apply your unique strengths to the situation. That’s fundamentally different from just copying your opponents.

An iconic example from tech history is the first iPhone: Apple observed that smartphones were not user-friendly and therefore didn’t appeal to mainstream users; it applied (orientation) its unique strengths, such as superior design and a modern Unix-based OS, to come up with a hypothesis (decide) that a phone with a huge touchscreen and a desktop-class OS would change the game; it worked tirelessly (act) on the implementation, finally launching the product in 2007. There were several surprising elements in the launch beyond just the product capabilities, such as unlimited data plans that Apple negotiated with mobile carriers. But then Apple didn’t stop, but came up with new rapid iterations: It launched the first app store; it refreshed the iPhone every year with new capabilities, some of them quite unique and surprising; and it applied the same technology to a bigger form factor, launching the modern tablet market with the iPad. Today, needless to say, Apple makes almost all profits in the smartphone market and just became the first trillion-dollar company, despite going up against competitors like Google who are masters of quick iteration and surprising strategic moves as well.

Thinking in structured, tightly managed iterations comes naturally to many startup teams as long as it affects technical development processes. But it is surprisingly rare in strategic planning and competitive positioning. Applying an OODA loop (or a similar approach – there are many modern variations) to everything from day-to-day operations to long term strategy is a very effective way to outperform your competition in highly dynamic markets.

There are many other highly relevant aspects in Boyd’s work that this blog post can’t cover. For example, he wrote extensively about the importance of a clear strategic goal and focus of effort (for which he used the German word “Schwerpunkt”) to enable decentralized units to come up with independent decisions within their own OODA loops. Every leader of a rapidly growing startup knows how important that is as you expand your team.

Again, I strongly recommend the excellent biography by Robert Comran, as well as this overview of many of Boyd’s most important works.