Anyone who (like me) was around for the original Internet boom of the late 1990s and is now witnessing the hype around Generative AI can’t help but see quite a few similarities.

To be clear, I have absolutely no doubt that generative AI is a generational technological breakthrough and will fundamentally change not only the IT industry, but the world — just like the Internet. But it’s also clear that what we’re currently witnessing in the Generative AI market is not sustainable — not from an entrepreneurial perspective and not for investors.

As they say, history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. So what are some lessons from the dot-com era that might apply to this new generation of technology as well — at least in some ways?

1. The most obvious technical challenges are quickly solved and lead to rapid commoditization.

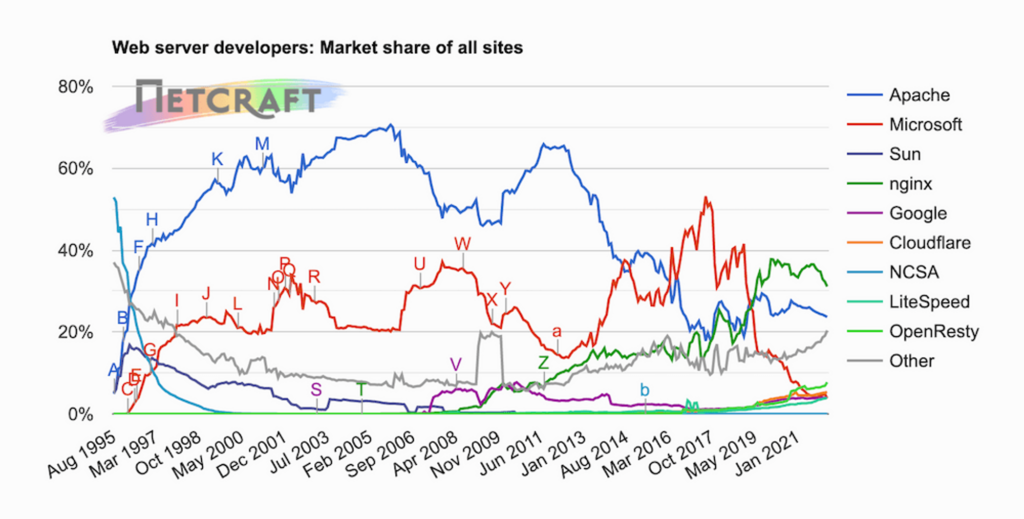

After Marc Andreessen and team famously created the NCSA Mosaic browser and later founded Netscape, dozens of browser companies popped up, trying to jump on the browser bandwagon. The same happened on the server side: Various new and old players quickly hacked together something that was able to serve HTTP requests and tried to sell these early products.

Those were the most obvious technical building blocks that were needed to create and expand the World Wide Web. The consolidation was swift and brutal. After just a few years, only two products were left that mattered: The open source standard Apache HTTP Server, and Microsoft’s Internet Information Server, which was a product that the dominant IT company bundled with Windows. The same thing happened on the browser side.

In the end, web servers and browsers turned out not to be a business — at all. It was simply too easy to build them, and in the end “free” and “free with existing distribution” won over slightly more sophisticated commercial products.

What’s the equivalent in today’s generative AI world? Could LLMs experience this kind of rapid commoditization? Right now that seems unlikely, since building top-class LLMs is very expensive and complex. But recent progress in open source LLMs at least suggest that the technological moat of the top players is not unassailable.

Makers of (relatively speaking) simpler tech elements — vector databases, programming frameworks, data loading tools come to mind — better look out below. Those who can find true differentiation can succeed, but the bread-and-butter stuff will soon be a free commodity.

2. Incumbents are often the early winners of a new wave because they have distribution. But they get replaced by better technology later.

It’s a myth that established player often miss a new wave of tech due to slowness. The dot-com boom was quite the opposite: Microsoft muscled its way into the industry by making its browser and server products free; AOL was the first path to the Internet for countless consumers; IBM plastered every available marketing channel with its “e-business” messaging; server makers like Sun and DEC sold more machines than ever; and Oracle had visionary ideas about “network computers” that would get all their software online — basically SaaS and Chromebooks avant la lettre.

All these incumbents managed to initially play strong roles in the Internet market. Microsoft even famously managed to kill browser pioneer Netscape and got into anti-trust trouble because of it. Minicomputer stalwart DEC for a while had the most successful search engine.

But after a decade or so, the incumbents started to lose out to new players with fresh, disruptive approaches. Sun and DEC became victims of Linux. Microsoft lost the browser war to Google. IBM lost market share to countless new service firms that implemented digital infrastructure without the weight of legacy technology.

We have seen similar developments in other tech waves. It’s hard to remember now, but 90s cell phone king Nokia for years dominated the smartphone market of the early 2000s before being replaced entirely by two newcomers to the phone industry, Apple and Google.

So who are going to be the strong incumbents in this generative AI wave that might run the risk of being replaced later? Microsoft, Google and Amazon are fairly obvious choices. They are all pushing their generative AI products on their customer base, and probably these products are good enough for now. But a huge technology wave like the current one typically produces so much innovation that it will be hard for these giants to keep up in the longer run.

Who will be the true disruptors who end up dominating the market? It’s very likely that they are still tiny or don’t even exist yet, much like that small search engine company that started in 1998 in a garage.

Startups and their investors therefore shouldn’t be overly concerned about early products from tech giants. They play a crucial role in getting the market used to the new technology, opening up countless opportunities for younger players in the process.

3. A new technology causes a Cambrian explosion in startup creation. Not many from the first wave survive and succeed.

Lycos, Excite, Infoseek, GeoCities, Yahoo, Pets.com Webvan, Commerce One, CMGI, eToys, Inktomi, iVillage, MarchFirst, Prodigy, Vignette.

Do any of these names sound familiar? If you are too young to remember the dot-com era, you might have heard of Yahoo, since it’s still around. Pets.com and Webvan are classic case studies for startup failure. But most of the other companies are long forgotten. What they have in common: They used to be a Really Big Deal in the mid-90s. Most had spectacular IPOs before collapsing just shortly thereafter.

That is, unfortunately, a completely normal phenomenon in technology. There once were hundreds of car makers and hundreds of PC makers too. In each category, only a handful are left.

Pretty much the only companies from this first wave of Internet startups that turned into category-defining companies were Amazon and eBay. There are some smaller success stories too, but it was hard to survive this first wave.

The biggest cluster of winners were the companies of the second wave of Internet startups, founded in the late 90s. Google, Priceline (Booking), Netflix, Salesforce, TripAdvisor, Baidu, Mailchimp and Akamai are some of the best examples. Of course there are similar examples from other tech waves too, most famously Facebook, which entered the social media game relatively late.

Why are these second-wave companies more successful in the long run than the early pioneers? I think there are two reasons. An early wave of hype creates many distorted incentives. The earliest Internet startups tried to profit from the craziness, went public as quickly as possible and often had built no real business to speak of. The second wave had to compete on real merits.

Secondly, there is of course also a learning effect. Google for instance, apart from having superior ranking technology, also didn’t make the mistake of its competitors of wanting to be all things to all people. The “portals” of the time were a chaotic mess, and Google decided to give users what they actually wanted: A clean, simple search box.

What does that mean for generative AI startups? While it’s tempting to chase the current overheated hype, thinking longer term is likely going to win over short-term opportunism. It’s not a coincidence that Amazon ended up being the defining company of the early dot-com hype because Jeff Bezos is well known for his long strategic time horizon. Generative AI startups should try to do the same: Think in horizons of five or ten years, not just up to the next demo day. And find investors who do the same.

4. “Roll your own” seems like a good idea in the early days of a technology. It’s not, and that’s where startups come in.

In the 90s, pretty much every interactive agency, almost every media company and countless traditional corporations built their own web content management system [1]. Why? Managing a growing website with the manual means of the day (basically hand-written HTML in Notepad.exe) quickly became impossible to scale. It seemed quite easy to take a database, a bit of templating code and some deployment scripts to put together something that was able to generate a more dynamically managed website. The result were thousands of half-baked content management systems.

The first steps were easy, the ongoing maintenance and scaling was not. The Web back in the 90s was rapidly evolving, and just keeping pace with the latest HTML and JavaScript features overwhelmed most of the organizations who had built a content management system (speaking from experience here: My company back then had one of those too and abandoned it after a couple of years).

Similar things were happening in web analytics, e-commerce infrastructure, JavaScript development, caching and other parts of the tech stack. This led to the emergence of several new categories of specialized providers. The content management market produced some successful companies such as OpenText or Day Software (now Adobe Experience Manager). There were some successful startups in all categories of the stack.

But similarly to other sectors of the Internet, these categories produced the largest stand-alone outcomes in the second wave of companies, for example WordPress or Squarespace in content management. Almost all of the first-wave companies ended up as acquisition targets for larger players like Google or Adobe, but in many cases founders and investors were happy with the results.

Of course we are currently seeing similar patterns in generative AI. It’s temptingly simple to take a programming framework such as Langchain or Llama Index, slap on a vector database, write a few GPT prompts and declare victory. Something that credibly looks like an “enterprise chatbot” can be put together in a weekend by any talented engineer (with the help of AI coding tools, obviously).

Many of these experiments are happening in the innovation departments of large corporations, as well as in consulting firms and traditional SaaS providers. What they have in common: They are unlikely to succeed once the thrill from the initial demo is over. Creating something that can scale in the long run is very different from putting together a cool MVP.

What’s going to happen? Corporate customers and consulting firms will fade out their internal projects and instead will buy professional solutions — probably a mix of products from trusted incumbents and cutting-edge startups. SaaS providers who want to add ChatGPT-like functionality to their products are going to dig a bit deeper into the tech stack, but they too will end up mostly relying on packaged solutions — very much like many interactive agencies and media companies ended up using highly customized versions of standard web content management software.

Solving the most challenging problems in the stack and coming up with truly reliable and scalable products is going to be one of the biggest opportunities for startups in the generative AI space. If history is any guide, there are going to be quite a few successful companies being created in this first wave .

The second wave — again, WordPress and Squarespace are good historical analogies — might be all about simplification and democratization. Realistically, implementing a truly capable LLM-based system is by far not achievable for smaller companies outside the tech sector. But it will be in a few years. This might create even bigger startups.

No doubt, generative AI represents a major technological breakthrough that will transform industries. But the current hype and excitement is unlikely to be sustainable for entrepreneurs and investors. The dot-com era (and other technology waves) demonstrated patterns like rapid commoditization of basic building blocks, the rise and fall of first-wave startups, and the risks of companies hastily “rolling their own” solutions. However, these lessons also point to significant opportunities, especially for second-wave startups that can leverage the learning, build differentiated solutions to complex problems, and potentially democratize generative AI capabilities over time. Avoiding the distorting effects of hype and taking a long-term, sustainable approach will be key for companies looking to harness the generational potential of this transformative technology.

[1] Thanks to Squirro co-founder Dorian Selz for pointing this out in the context of LLMs.