Being an entrepreneur, particularly a founder of a fast growing tech startup, is obviously a hard job. Anybody who chooses this career is probably aware that it comes with long hours, many ups and downs and plenty of challenging situations.

Entrepreneurship traditionally has a culture of relentless optimism. Ask any founder how they’re doing, and they will probably tell you that everything is great. Killing it. Growing like crazy. Super excited about the progress. This mindset is of course needed to build a company and conquer all the many obstacles that a startup faces. Founders, CEOs in particular, have to project optimism to convince customers, employees and investors that this is going to be the best company ever.

But this often obscures the fact that life as an entrepreneur is challenging — particularly if you are expecting to have a personal life outside of your professional existence. This tension leads to many potential issues — mental health is a challenge for startup founders, and much has been written about that. But even on a very practical level, balancing the demands of the job as a founder with other needs is difficult. This article is an attempt at giving some pragmatic, tangible advice from my 25 years of experience as a tech entrepreneur.

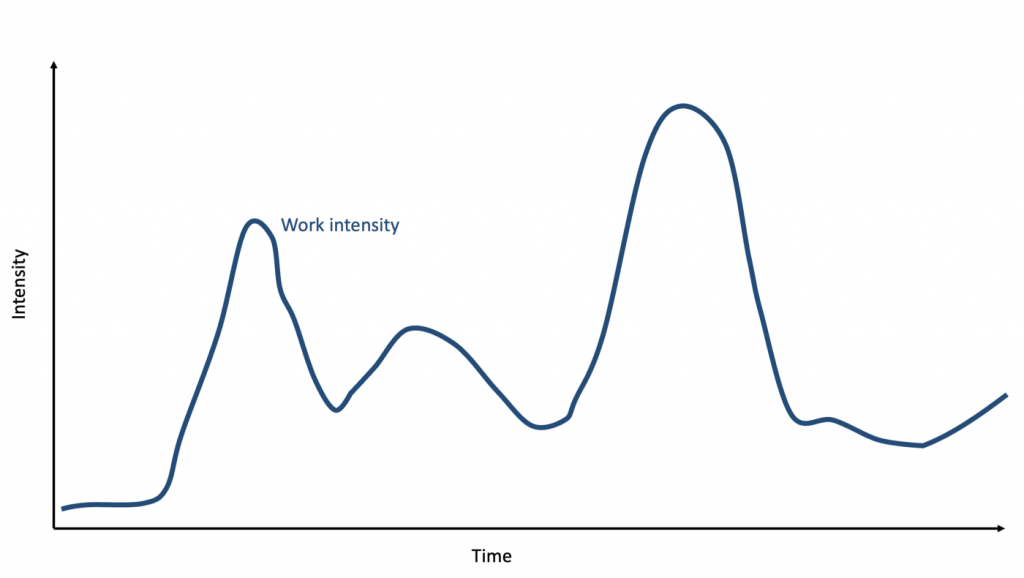

Typical work situation of a tech entrepreneur

Why balance?

First of all, contrasting “work” and “life” might sound wrong to many entrepreneurs. If you chose this path, you are probably so fascinated by your work that it seems very natural for you to spend most of your waking hours on it. But doing nothing but work can have negative consequences quite quickly. I’ve seen plenty of burn-outs in my entrepreneurial career, and I was close a couple of times myself. Burning the candle on both ends is not a good idea; the consequences could be catastrophic for both you and your company.

On the other hand, the term “work-life balance” is sometimes misinterpreted as “going to yoga class in the middle of the day, enjoying long weekends every other week and taking six weeks of vacation in the summer”. Some entrepreneurs feel like losers if they can’t squeeze flexibility like this into their busy schedules. But that’s a cliché view and doesn’t represent the truth about life outside of work at all.

“Life” is not monolithic

To understand the topic more deeply, it’s first of all useful to distinguish two categories that make up the “life” part:

- What I would call mandatory life activities: Taking care of children or aging parents; your own medical challenges or those of people close to you; mandatory civic duties; life logistics such as moving; personal financial stuff. The “mandatory” doesn’t mean that some of this can’t be enjoyable and rewarding. It just means that you can’t get out of it even if you wanted to.

- Optional life activities, aka the fun stuff: Spending time with family and friends; travel; exercise; culture; dating; going out; volunteering; hobbies; etc.

Now some of you might say something like “Exercise/travel/culture etc. is not optional, I need to do this stuff to live”. Let me guess: You are in your twenties or thirties, currently have no direct dependents and have probably yet to experience a real crisis in your business. When push really comes to shove, pretty much everything that seemed non-optional but really isn’t goes out of the window very quickly. The trick is in making sure this only happens if it’s really necessary, not by default.

Work and life come at you in waves

The second aspect to understand is that work demands in entrepreneurship are anything but constant and linear, but come in waves. And the peaks can be very high. When you’re raising a new round of funding, launching a new product, entering a new market or dealing with a major crisis, the demands can spike very suddenly and consume most of your time and energy.

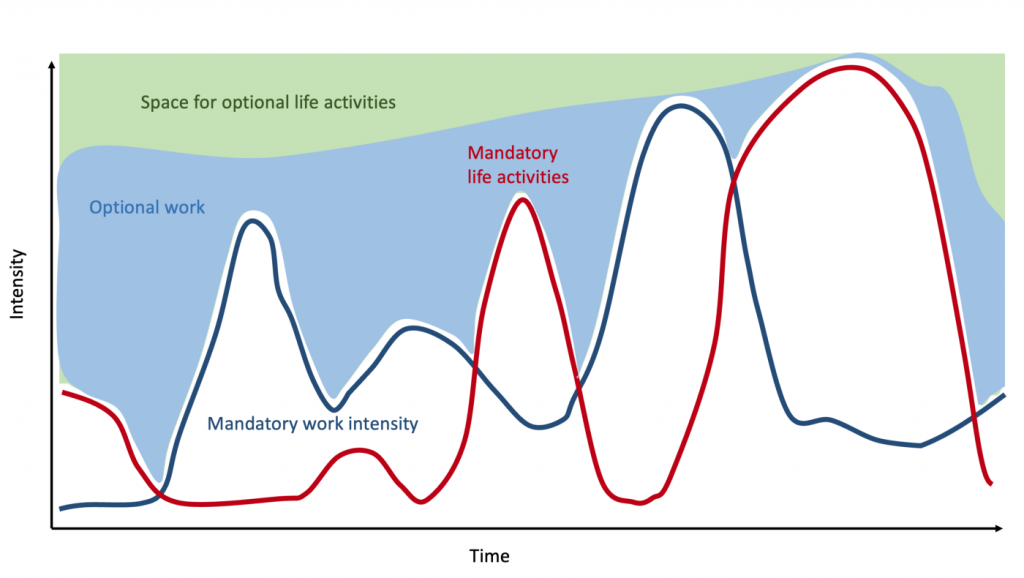

It might look something like this:

It’s no coincidence that I painted the work demands as very low at the beginning. When you are just in the idea phase of a startup, things can be objectively very quiet, even if the phase feels intellectually intense and emotionally challenging. But you don’t have to deal with customers, employees and investors at this point, so there are very few inflexible external demands on your time. This can change very suddenly once you start hiring a team, raise you first funding and get your first paying (and therefore demanding) customers.

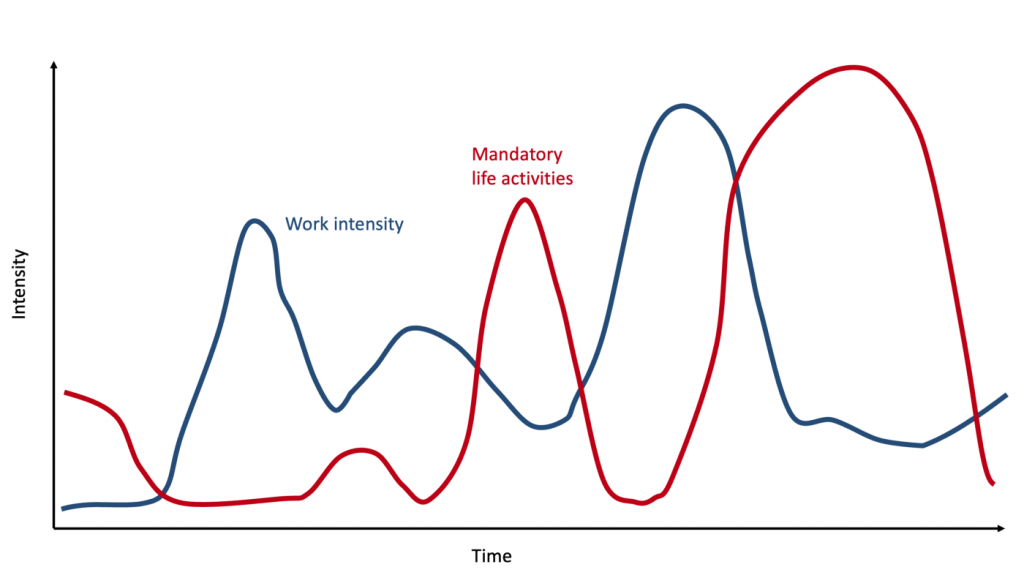

The mandatory life activities have a habit of coming in waves as well, maybe something like this:

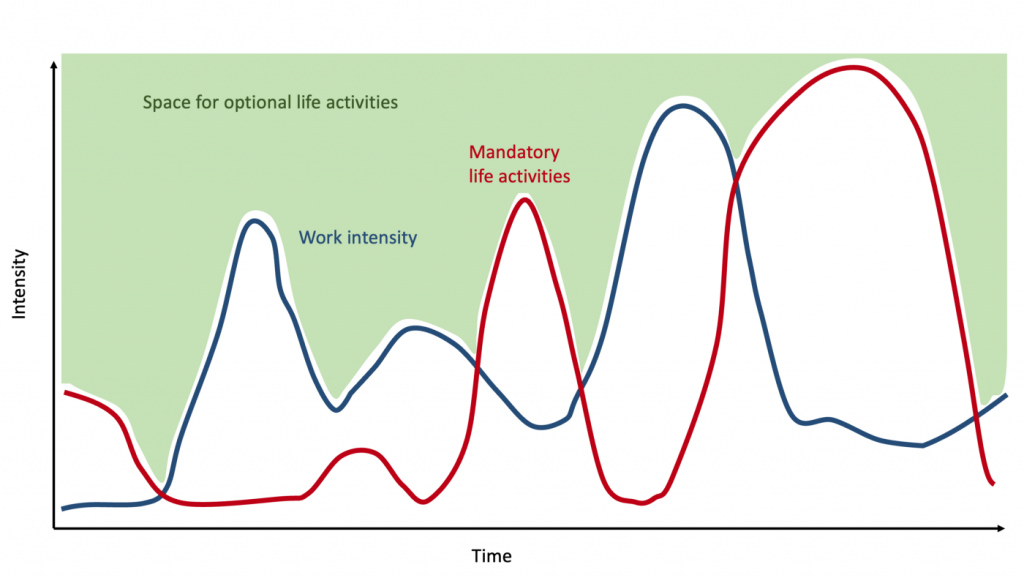

And this of course means that the amount of space you have for optional life activities is pretty much a function of whatever remains after work and mandatory activities took their share:

Now this (admittedly clumsy) graph shows a number of fairly typical cases. Sometimes work is intense, but the rest of your life stays out of the way. Sometimes mandatory life activities consume the majority of your attention, but fortunately work is a bit more quiet. And then sometimes both categories explode at pretty much the same time, leaving very little room for other stuff.

Optional work — the only variable

One more thing is very important: The “work intensity” curve above refers to the work that you absolutely have to do to keep things going. Of course it’s easy to fill your entire time with work if you’re a founder — what I would call “optional work”, even though it often might not feel optional at all. There is always plenty to do to move your company ahead. Work at a startup never runs out.

And of course this kind of work takes away from only one component: optional life activities.

Four brutal truths

There are four brutal truths about these curves:

- The amount of “optional work” you do is the only variable that you can really control. The rest just happens to you.

- The level of mandatory work in a startup is much, much higher and far less predictable than in a corporate job.

- Entrepreneurs experience the same amount and volatility of mandatory life activities as everybody else. Your life doesn’t care if you’re in the middle of a product launch.

- You never really know if the amount of “optional work” you did was enough. Could you have won that customer or convinced that investor if you had just spent another hour refining that deck on the weekend?

This last point is the most challenging in managing work-life balance for entrepreneurs: In stable corporate jobs you typically know quite well how much work it takes to reach your goals and get ahead (even if the level might be pretty high, such as in investment banking or consulting — it’s still fairly predictable). In entrepreneurship, the uncertainty is much, much greater.

Different situations need different patterns

I have had the privilege of living through several of these different situations in my own career. Specifically:

- In my mid-twenties: Co-founder of a young, rapidly growing startup, no real other obligations. Worked long hours, frequently experimenting with new stuff.

- Early thirties: CEO at the same company, but going through a painful turnaround after the dot-com bubble burst. Few other obligations. Very long hours putting out fires, mandatory work nearly at 100%.

- Mid-thirties: Going back to a zero-stage startup situation, just two guys in a room writing code. Aging parents and some other complexities. Reasonably long hours, with plenty of flexibility and room for innovation.

- Early forties: CTO at a VC-financed, rapidly growing company. My wife and I just had kids; sick parents and various other life challenges. Long hours on all fronts just to keep things together, very little room for anything else.

- Late forties: Changed career to VC, school-aged kids, other things mostly stable. Still demanding hours, but good flexibility and time for learning and innovation.

Out of those, 2 and 4 were the most stressful by far, driving me close to a burn-out. In retrospect, phase 4 made phase 2 look like a walk in the park, but that’s another thing to recognize: Over time, you (hopefully) learn how to deal with demanding situations and build resilience.

One insight from these different times was that perceived work-life balance is not a function of hours that you objectively spend at work. In phase 1 I did little besides work, and yet it didn’t feel like I was missing out. The important thing is to observe your own needs and try to adapt accordingly.

Some concrete tips

What can entrepreneurs do to not let their lives be consumed by work, but at the same time use their time and energy as effectively as they can to build a business? Here are a few tips.

- Accept the reality that the mandatory demands on your time come in waves and can’t really be influenced. Be realistic about what they are and plan ahead.

- Talk to people who have been in these situations before to get a realistic view. For example, many young entrepreneurs are surprised by how time-consuming fundraising can get. And people who have kids for the first time are often shocked by how intense raising young kids is. Entrepreneurial peer groups such as the ones offered by the Entrepreneurs’ Organization (EO) are a great way to learn from others, for example.

- Segment your tasks into four categories:

- Essential, mandatory work (things will go wrong if I don’t do this)

- Important optional work (important to do because it will move things ahead)

- Unimportant optional work (nice to have, but am I doing this just to look busy?)

- Learning and networking (not immediately urgent, but might benefit from it later)

For most people, the last category gets cut first, and in the long run that’s a mistake. Some people on the other hand put way too much time into the last category because it’s the easiest.

By assigning time budgets to each category consciously you can make sure to keep a balance. And obviously keep the sum low enough to leave room for optional life activities. - Optimize for optional life activities that are granular and can easily fit into an entrepreneur’s busy schedule. It’s great if your hobby is kayaking in the Antarctic, but that’s probably not going to work all that well with the demands of your job and rest of your life. It’s much better to optimize for fun activities that can be fit into a couple of hours or so at a time. It will make it much easier to actually do those things.

- One of the great things about entrepreneurship is that you can shape the culture of your company. Make sure to do this consciously with regard to work-life balance. Some companies have a culture of long work hours just for the sake of it, and that can be destructive in the long run. I wrote more about this topic here.

Finally, even at the risk of triggering an “OK boomer” alert, some advice for younger readers: When you are young and have few obligations, make sure that you use your time to learn and experiment a lot. It will tremendously help you later in your career. And yes, that might mean spending a lot of long hours at work instead of enjoying optional life activities.

I can still point to Sunday afternoons or late evenings spent tinkering with some new technology or exploring an interesting new concept that ended up changing the course of my career. What about the fun events I missed because of that? I don’t remember what they were.