The last forty years have been a spectacular period for technology entrepreneurship. A rapid succession of fundamental technologies from the personal computer to the world wide web to smartphones (and their many underlying layers of enabling technologies) have produced a cornucopia of entrepreneurial opportunity. Today, the five most valuable companies in the world are all tech companies, ranging in age from 42 years (Apple) to 14 (Facebook). These and many other companies have not only generated enormous amounts of wealth, but very tangibly changed the world.

For anybody who wants to be a technology entrepreneur, the question arises: What will the next ten, twenty, forty years be like? Will we see more waves of opportunity, comparable with the past four decades? And in what field are the most interesting opportunities, how can you find a strategy that works?

On a very positive note, the entrepreneurial ecosystem in much of the developed world has never been more advanced. You can start companies in many places in the US, Europe and Asia and get ready access to capital, talent and research. Global VC spending has never been higher. Entrepreneur-friendly co-working spaces now exist even in relatively small towns. Most of all, entrepreneurs probably enjoy more respect in society than ever before. It’s not an exotic wish to start your own tech company anymore, it’s seen as a really cool career choice.

Furthermore, tech entrepreneurs can build on rich platforms, ecosystems and foundational technologies. A company like Uber would have been impossible before the arrival of a mature smartphone industry with highly capable end-user devices, near perfect connectivity and easily accessible app distribution systems. With today’s cheaply available cloud computing infrastructure, it’s easier than ever (at least from an infrastructure standpoint) to build online applications in all kinds of sectors.

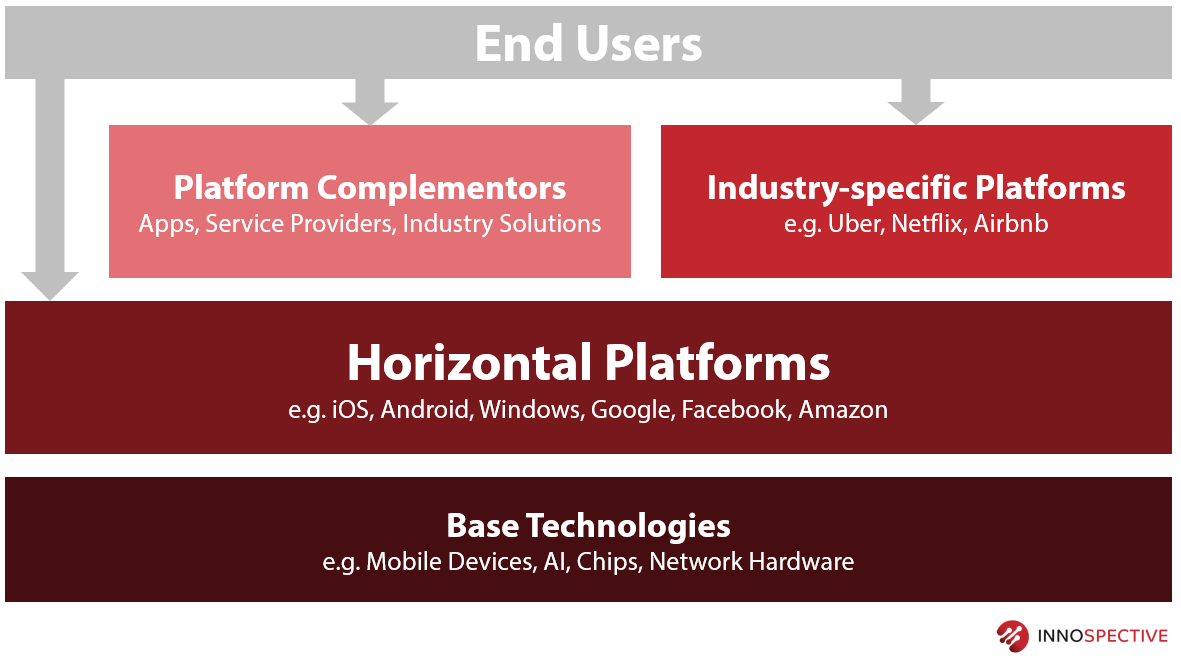

Let’s look at a simple framework of company types to locate the kinds of opportunities available today:

At the center of power are the horizontal platforms that offer a broad set of capabilities that others can build on. The dominant technology giants all play in this segment, and that’s where the biggest fortunes are created.

They rely on a variety of base technologies that they typically don’t control directly, but they might play in some of these areas (e.g. Google making its own phones or AI frameworks). Base technology companies commercialize deep research, often providing essential new capabilities to other market participants.

On top of the platforms are platform complementors who use the platform’s capabilities to provide their own solutions to end users. These could be individual apps, services such as SEO or system integration, or specific industry solutions in the B2B environment, for example a payment product.

A particularly interesting field are the industry-specific platforms that use the horizontal platforms as a foundation to build their own two-sided marketplaces, bringing together supply and demand in a particular industry, often disrupting existing market structures.

There is plenty of entrepreneurial opportunity in all these fields, but they’re not equally accessible and not equally attractive. Let’s look at the details.

Base Technology

The foundational technologies behind our modern tech world are still racing ahead. While the speed of traditional CPU’s hasn’t been increasing as quickly as in the past, new ways to perform tasks like the use of GPUs for machine learning have dramatically improved. Network technology is rapidly changing as well, both mobile and wired. And artificial intelligence is probably the most visible space where innovation happens faster than ever.

Having a successful startup in these base technologies can be very lucrative. For example, even comparatively small AI startups have been acquired at extremely rich valuations over the past few years. Startups that can build the proverbial “secret sauce” in tech — real intellectual property — are typically very sought after.

However, there are two major pitfalls. First, building a company in this space tends to take a long time and is typically very capital-intensive. This is not the type of company that two guys in a coffee shop with an AWS account can build. You will need access to deep research capabilities, and that’s expensive. Second, many segments tend to be dominated by very large incumbents. Also, the large platform players are increasingly playing in base technologies, particularly AI, so it could be that you’re going up against very powerful competitors in this segment. On the plus side, these incumbents can be perfect acquirers for a technology that fits into their portfolio.

Horizontal Platforms

The largest fortunes in technology are traditionally built by large, market-dominating horizontal platforms. The top five – Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft – are all dominant players or near monopolists in a particular business segment that has the characteristics of a broad platform. They’re not simple products, but rather offer a broad solution that enables customers and third party vendors to transact with each other in some form or shape. The business models that allow for the extraction of value from these platforms vary, but they all have in common that they are two-sided or multi-sided markets.

Building this kind of universal platform is probably harder than ever. It has always been a very long shot – one of these dominant companies comes along once or twice a decade at best. These markets have a strong winner-takes-all characteristic, which means that for the one lucky winner there will be many losers trying to do the same thing (remember MySpace, BlackBerry or AltaVista?).

Remarkably, the top platform companies nowadays are incredibly well run. Previous generations’ dominant companies like IBM or Digital Equipment all lost their dominance (or went out of business altogether) because they were disrupted from below. Today’s technology giants are clearly very aware of the dangers of disruption. They all have in common that they defend their main turf aggressively and successfully against potential new entrants.

Facebook is probably the most striking example: It paid very rich valuations to acquire threatening startups like Instagram, WhatsApp or Oculus at a relatively early stage. Anything that looks like it could become an important platform somewhere close (or even not so close) to Facebook’s core business either gets swallowed up or attacked very aggressively, as in the case of Snapchat. Mark Zuckerberg clearly knows his technology history, and so far, this has worked well for him.

All top five companies invest aggressively in new technologies that don’t necessarily have much to do with their core business, but could be the next big thing, often going deep down into base technologies or upstream into applications: Amazon, Microsoft and Google dominate cloud computing. Facebook and Google dominate virtual reality, and together with Apple, augmented reality. Amazon and Google dominate voice assistants, with Apple and Microsoft coming in as also-rans. All invest heavily in artificial intelligence, both to make their core products better, but also to extend their platform reach.

This means that it has become much harder for potential platform companies to grow to a level of dominance that could endanger the existing giants. Building platforms is extremely risky and capital-intensive, and most VCs will happily take something like Oculus’ or Instagram’s early exits instead of betting everything on a highly unlikely outcome.

Platform Complementors

But what if you want to build a company on top of these platforms as a platform complementor? It’s a time-tested recipe. Microsoft’s Windows platform alone has an ecosystem that generates over half a trillion dollars in annual revenue for partners, according to the company. Apple’s app store last year generated about $26.5B in revenue for third-party app makers — small compared to Apple’s own revenues, but still more than half of what the entire global movie industry made in box office revenues. So there’s clearly plenty of opportunity to be had.

There’s a catch: All the dominant horizontal platforms today are walled gardens to some extent. They have rules that are controlled by the platform owner exclusively, and there are no guarantees that the platform owner will not suddenly turn out to be your competitor.

It’s by now a familiar pattern: Platforms let third parties build products on top of them. These vendors often fill the holes that the native platform still had, providing functionality that makes the platform more valuable. If something becomes successful, it will either be copied by the platform itself, or it gets acquired. It has been said that each of Apple’s iOS upgrades kills a few dozen startups because the native platform suddenly provides something previously offered by third parties. Typically, the platform default wins over the independent solution, even if it might be worse.

On the positive side, the platforms frequently acquire interesting startups that provide a clever solution, but valuations are not often tremendously rich. Given the threat of an outright competitive situation with the platform owner, many third-party startups prefer a mediocre deal over the long-shot bet at surviving on their own. Facebook for instance as a relatively young company has acquired 66 startups so far, most of them at an “undisclosed” valuation (which is VC speak for “not a great deal that we could boast about”).

There are segments that the platforms tend to leave alone, mostly in services or particular B2B market segments. But these are often sectors that are not very scalable and therefore not relevant for global platforms with their tremendous mass-market reach. While it is absolutely possible to build sizable and very profitable companies of this type, it’s usually not the world-changing opportunity that the most ambitious tech entrepreneurs strive for. It’s a pattern of more moderate rewards for moderate risk.

Industry-specific Platforms

This is a segment that has seen tremendous growth over the last few years. Companies like Uber, Spotify or Airbnb transform industries one at a time, not so much as core technology companies but as advanced, disruptive users of technologies. Entrepreneurs who are interested in this kind of recipe are in a better position than ever before. There are plenty of industries still waiting for disruption.

There are two main challenges in this segment: Many traditional industries tend to be static and highly regulated, so startups often have to deal with red tape and government intervention — witness Uber’s countless issues around the world. Furthermore, even large industries often only have space for one or two dominant players. There’s Uber and Lyft, but nobody else matters (in Western markets). Getting to a dominant position quickly is key. For these two reasons, this type of company tends to be very capital-intensive in order to support rapid growth and deal with market inertia and regulatory slowdowns. The biggest ones raise capital in the billions, and that’s obviously not easy to get. Most of these companies have still not reached profitability and depend on continued inflows of capital, and that’s an uncomfortable position for an entrepreneur to be in. This is a very high risk, high reward kind of segment.

Pick Your Battle

The bottom line is: today’s technology industry is a very mixed bag for ambitious entrepreneurs. There is plenty of opportunity in industry-specific platforms for different segments of the economy that are still largely undisrupted. Unicorns like Netflix, Uber, Spotify, WeWork or Airbnb have shown how to do it. There is also plenty of opportunity in deep base technology that might become a necessary building block for somebody else, but this type of company takes time and deep skills.

Being a platform complementor is probably the most varied case. There are niches that can be enormously lucrative. Good examples exist in the app market for gaming and specialized messaging. B2B solutions can be very successful, as illustrated by giants like Adobe or SAP, or more recently Stripe and Slack. It’s always possible to build a solid services business as well. But if you fall into the trap of just building a complementary feature for a platform, the lifespan of your startup could be very short.

Finally, building the next big horizontal platform — being the next Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg or Larry Page — is harder than ever. The top tech companies move so quickly and with so much might into new technologies — blockchain is the most recent example — that even the nimbleness of a startup is not sufficient. These guys are not IBM, Blockbuster or Nokia. They’re giants, but they’re very nimble giants, and that’s not exactly a comfortable type of competitor for startups.

Is Now the Time?

To get back to the question in the title: Now is probably as good a time as any to start a tech company. The infrastructure in technological, financial and institutional dimensions has never been better. Its easier and cheaper to start a company than ever.

Furthermore, there are exciting new technologies out there that are still early enough for a startup to make a dent, but advanced enough to provide a real market. AI, VR/AR, robotics, IoT and maybe blockchain come to mind. Startups can provide real value in these fields or build new applications and services on top of these capabilities.

However, the risk profile for tech startups is now quite a bit different than a decade ago. While there have always been dominant companies in tech, we have never seen a time when five almost equally strong tech giants dominated the market so much. They are broader, deeper, nimbler and more ambitious than previous giants.

This requires startup founders to think very carefully about how to play with these whales because they could crush your little startup boat at any time. A deep understanding of platform strategy is now a required skill for founders and their investors.